Six days in 1945

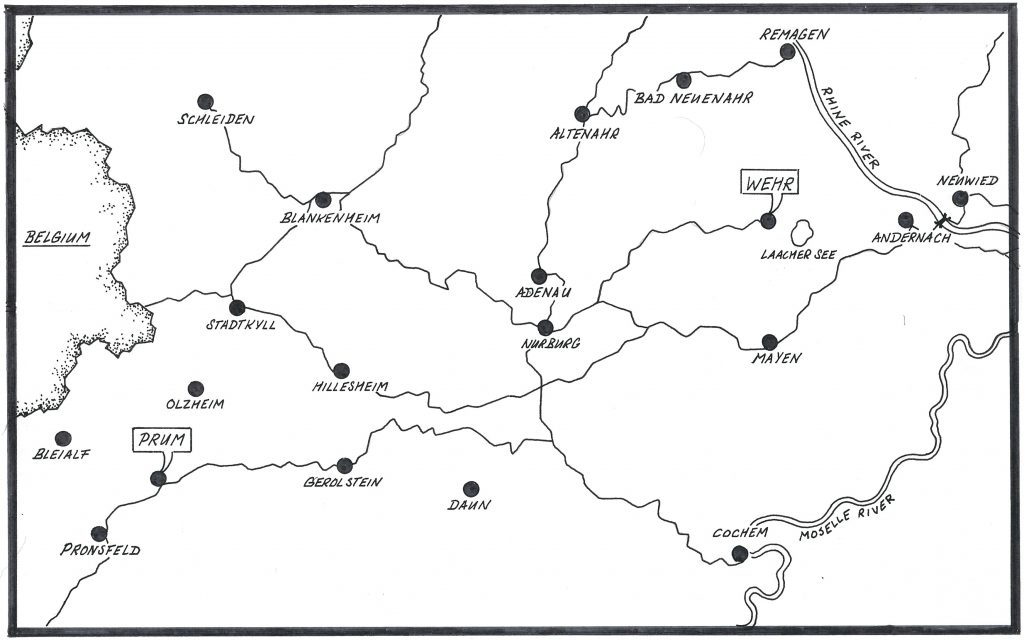

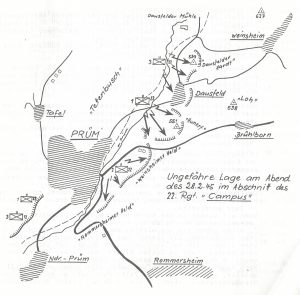

This story is written by Edwin D. Williams in 1992, member of F Company, 2nd Battalion, 22nd Infantry Regiment. This first-hand account tells what Williams experienced while his company attacked the “Prümer Held” woods east of the city on the first day of the Lumberjack offensive, February 28th, 1945. As the attacking companies climbed up the wooded slopes opposite the town of Prüm, the Americans were struck by a strong counterattack from the Fallschirmjäger-Regiment 14. During the confusing battle in the dense forest, Williams and another soldier were separated from their unit, and finally captured. The story continues with a march in captivity, with an extraordinary outcome.

All credits go out to Edwin D. Williams and Bob Babcock.

“I’ll start my story by telling you of the events of the day before my capture. I believe this was Feb. 27, 1945, although I’m not sure. Most of the time we didn’t even know what day of the week it was. I remember the day was dreary, with a cold, light rain falling. We had been in contact with the Germans for many days, driving them back into their homeland, and they would stop and put up heavy resistance, when they could. This day we were moving up. The going was tough. The terrain was extremely hilly, rocky and wooded. I was not only carrying a full field pack, as a mortar section squad leader, this day I was carrying the 60mm mortar, all 60 pounds of it. In basic training we would break it down into two components, namely the barrel and the base plate. In combat it was a different story. What the hell good would only half of it be if the man carrying the other half would be hit? We kept it in one piece. All the other members of the squad carried 12 rounds of 60mm shells in a heavy canvas pouch slung over their shoulder, 6 rounds in front, and 6 in back, and we would change off on occasion. My only personal weapon was a Colt 45.

Late in the afternoon we reached what everyone supposed was our objective, and we were told to “dig in”. Digging a foxhole was normal procedure every time we stopped. I dug a hole back into a hillside, just big enough to get into, in a sitting position. The digging was difficult in that rocky terrain. I covered the top of the hole with my shelter-half, throwing dirt around the outer edge to hold it in place. Finished, I crawled in to rest; I was beat and hungry. I reached into my pack and pulled out a “K” ration. The beverage powder in this one was lemonade, so I figured to heat some water, so I could at least drink it hot. I was heating a canteen cup of water over a small fire made by burning the waxed box of the ration. About the time the water was hot enough, someone walked past the hole, shouting “OK men! Load up!, We’re moving out!”. I’m sure you can imagine what words passed my lips, and what thoughts went through my head at that time, but in the military you learn very soon to take order without question. In disgust, I threw out the hot water, put out the fire, and crawled out. I retrieved my shelter-half from over the hole, picked up my load once more and fell into line.

We moved out, with conditions as miserable as before. Shortly another factor was added, darkness. It’s hard to keep up in single file in daylight, in darkness it’s virtually impossible, especially in rough terrain. We walked and struggled ahead for what seemed like three hours. The order to move ahead, very quietly, came down the line. We moved up for about half a mile. By up, I mean up hill. The terrain finally flattened out slightly, and once again we were told to “dig in”. Sergeant Kelly, our platoon sergeant, showed me where I was to set up the mortar, gave me a compass azimuth, and range, to where the Germans were. They were on the next hill, in the woods. I don’t think that there was a single foxhole dug that night. We were almost too tired to move, let alone dig a foxhole. I managed to scrape out a place to lay down, about six inched deep, threw my shelter-half in the bottom of it, laid down under my two blankets, and immediately went to sleep. I don’t think many, if any stood guard that night. At that point I didn’t much care. I don’t think I could have found the mortar in the dark anyway.

Awake at daybreak, while eating cold “K” rations, we were told that an artillery barrage was going to start on the wooded hill next to us, and when the barrage stopped we were going to attack. Somehow our company jeep found us and brought up cigarettes, free cigarettes, not just a few, three cases. Everyone had all the smokes they wanted and then some. Many cartons were left there on the ground. The artillery attack started on time and lasted about forty -five minutes. None of us thought many of the Germans could survive such an attack. Our 105’s were sure putting it to them. I’m sure our Company commander thought they were softened up enough when we attacked, but we found out different. In normal situations, when the rifle platoons attacked, the mortar squads stayed back in case they were needed for supporting fire, not right in back of the rifle platoons, where their effectiveness would be lost. For some reason we were ordered to follow the rifle platoons into the attack.

We took off, at a run, down the hill, across a small stream in the valley and up the ill-fated “Queen Hill”. This day I was carrying a pouch of mortar shells. About the time we caught up with the others, almost to the top, the Germans opened fire, pinning everyone down. We crawled up behind some boulders, wondering what we were going to do. I was also wondering what good my Colt 45 was going to do in this situation. A few minutes later our Company commander come running down the hill, jumped in behind the boulders and said, “Tie in with the first platoon”, and pointed to our left flank, and off to our right flank he went. I must have been the only poor S.O.B. to hear the order, as I was the only one that moved out. As I was running to my left, I picked up an M1 rifle, apparently dropped by one of our riflemen when he was hit, as there was quite a bit of blood around, but he was nowhere to be seen. Now I had a rifle but no ammunition for it, except what was in the clip. By pulling back the bolt I could see three rounds, so I knew I had at least three shots.

I continued in my direction until I saw two men I knew of the first platoon. They were the B.A.R. (Browning automatic rifle) team, and were the last men on the right flank. I positioned myself on their right, about thirty yards away, which made me the last man in that line. No telling where the next man to my right was. At this point I could not see any of the enemy. From my position I could not hear any verbal orders, but soon one of the B.A.R. team motioned that we were to move forward. I carefully arose and started moving. To the left I could not see any more of the platoon, as they were over the edge of the hill and down. We hadn’t moved more than one hundred yards when firing started down in their area, and since they were meeting resistance, we had to stop once more. Visually scanning the terrain ahead, I thought I was seeing flickers of movement, but no visible targets when the movement stopped. I knew I wasn’t seeing things, so every time I saw movement I squeezed off a round with the M1. The B.A.R. team was throwing some lead too. After firing I would pull the bolt back to see how many rounds I had left. I was getting no return fire at this time, but I was woefully short of ammo. Shortly I glanced to my left, and one of the men there was motioning as if to say “Come on!” I took a good look around before moving, thinking they had seen something I hadn’t. Seeing nothing, I gathered my gear and got ready to move, looked left again, and they were gone, to where and what direction I had no idea.

This is the point in time where an error in judgement probably led to my capture. I assumed they had withdrawn to the rear, to where we had come up the hill, but no, they had withdrawn to the left, the shortest way off this loaf shaped hill. This I learned later. I jumped up, throwing the pouch of the mortar shells over my shoulder as I ran. I hadn’t taken more than a few strides, when the Germans started shooting at me. Bullets were digging up the balls of leaves and dirt at my feet, and kicking bark off the trees around me. I ran in a zigzag pattern, to make myself a more difficult target. The firing finally eased off. At about the same time I saw and heard Pfc. Edward K. Zimmerman of the third platoon. He was their radioman and at this moment he was holding the walkie-talkie by the antenna and beating it against a tree as hard as he could. I figured what was going through his mind. Rifle fire began again and we took off running, until it eased off.

We stopped behind a large tree to rest for a moment and try to collect our thoughts. We both took off at the same time, running in zigzag patterns, until the firing stopped completely. We ran on together for perhaps another five hundred yards before spotting an empty German foxhole. It was plenty big and just too inviting to both of us, to pass up. We were, at that moment facing the fact that we were separated from the rest of our company, and didn’t know what the hell was going on. The foxhole was partially covered with logs and dirt, and as I mentioned before, plenty big, and as foxholes go, a thing of beauty. We were almost certain that the Jerry’s hadn’t seen us jump into the hole, as the firing at us had stopped a long way back. We both agreed that our best chance was to stay put. We still thought that our company had gone the same general direction we had, and we fully expected that they would move on the hill again, and we could fall in with them when they did.

We stayed down very low in the hole, and only spoke to each other in whispers. We both realized that we could be taken prisoner and Zimmerman was getting rid of all his German souvenirs by stuffing them between the logs and dirt at the top of the hole. I didn’t have anything to hide, but I loosened the strap on my wristwatch, and pushed it up as far on my arm as I could. The watch had been a gift from my mother, given to me before I left to go overseas. Everything was very quiet for perhaps fifteen minutes, then in the distance we began to hear conversation, so faint we couldn’t tell if it was English or German, but shortly we found out. Germans, who ordered us out in no uncertain terms, quickly surrounded the hole. These guys were German paratroopers.

Plenty scared, we crawled out and raised our hands. First they took our weapons, and then started searching our pockets. In the left breast pocket of my fatigue jacket I was carrying perhaps fifteen or so letters from my wife. After writing me a letter, she would put on fresh lipstick and kiss the last page, above her signature, and these letters I cherished. The Germans soon had them strewn all over the ground. They missed the watch this search, but took all the cigarettes and rations I had in my possession. While the search was going on, I glanced around, and then realized why we were unable to see any definite targets earlier. Their uniforms were totally camouflaged, even their helmets. They weren’t wearing the regular German Wehrmacht helmets, the ones with the brim dropped down above the ears. These were made like round pots. These people were rough, and rough looking. At one point I saw one of them eye/balling my snow pack boots, and I started to wonder how I was going to get my feet into the hobnailed boots he was wearing, if he insisted in a trade.

I can´t say we were mistreated, but there was plenty of shoving and shouting as they started taking us back up the hill. I took one last look back at all the lipstick/imprinted letters on the ground and silently said “Goodbye” to my wife and daughter. At that point I honestly thought I was never going to see them again. As strange as it was, they let us keep our steel helmets. When we took German prisoners, we always made them throw their helmets away, so they could not be used as a weapon. Zimmerman and I said nothing to each other during this time. We were sure that they would look in disfavour on any conversation between us. When we got on the top of the hill we could see how the Germans had survived the attack our artillery had laid in on them. There were many log-covered foxholes in the area. There had been casualties however, as there was a severly wounded German soldier lying on the ground. From the bandage he had on, and the amount of blood, it was evident he had a good portion of his left lower jaw blown away. The fact that he was there probably saved us from being executed, as they indicated they wanted us to carry this man down the backside of this hill. We learned later that when this hill was finally taken, they found the bodies of eight members of our company, who had been lined up and shot.

The only way we had to carry this man was between us, on two shelter-halves, buttoned together. The German shelter-half differed from ours, as theirs were made in sort of a triangle shape, where ours were rectangular. They buttoned two of them together, and somehow got it under this man. Before we could pick him up, our artillery started shelling this hill again. Now we were on the receiving end of our own artillery. Our “105’s” had a different sound than the German shells, when they exploded. These had a much sharper “crack” to them. By instinct alone, both Zimmerman and I “hit the dirt” when we heard the shells coming, but strange at is was, the Germans just sort of hunkered over, near a tree if possible. After the first barrage, our captors let us know in no uncertain terms that we were to get moving with the wounded man. Zimmerman and I twisted the corners of our makeshift carrier to give us something to hold on to, and picked him up. He was a big man, probably close to one hundred and eighty pounds. It felt like a ton. I’ll never know how we made it down to the base of thus hill, as they only let us set him down twice to rest, and then only momentarily. When we picked him up the third time, the shelter-half on my side began to tear, and we almost dropped him. I had to reach under him and grab hold of the un-torn edge, and hold on like that the rest of the way down.

There was a road running along this side of the hill, and across the road was a medical aid station. It consisted of a large bunker dug back into a hill and reinforced with logs and dirt. This is where they took the wounded man. They couldn’t do a whole lot for him except change the bandage. Their medical supplies were practically non-existent. This we learned after it was indicated to us that inside this bunker was where we were to stay. We sat on a bench along the wall, straight back from the door opening. The wounded man was in a bunk directly across from us. His breathing was short, and had a rattling sound, which got continually worse. It was clear that he was choking to death on his own blood. His breathing got shorter and shorter, and finally stopped altogether. The German medic finally came to him and seemed surprised to find that he was dead. I spoke to him in my best German and told him that he had been dead for about ten minutes. He and another medic then started going through his pockets, to see what they could find. Zimmerman and I spent the rest of the day in this bunker. We didn’t carry on much conversation, I’m sure we were both wrapped up in our own thoughts, wondering what our fate was. We also knew that most Germans could understand and speak some English. One of these medics could, we learned, when he said to us, “For you the war is over, Ya?” At that point we had to agree.

Darkness had set in when they finally took us outside. There were many German soldiers around. There were also three more members of our company, who had been captured. They were Sgt. Frank Ferranti, Pfc. Lawrence E. McCollam, and Pvt. Lai K. Wong, a Chinese American had been shot through the left upper arm, and was in a lot of pain. All the German medics had done for him was wrap his wound and put his arm in a sling, as they had no pain killing drugs. There was now some slight comfort in the fact that others had been taken prisoner too, and so far our lived had been spared. It was clear that we were getting ready to move out deeper into German territory. A second search was made at this time. The man to search me was smart enough to feel farther up my arm, and he found the watch. I spoke out and made it known to him that the watch was from my “Mutter”, but to no avail. We moved out with a fair size group of German troops, in what had to be an easterly direction. Thinking back now, we walked between three and four miles back, and into a fair size town (probably Fleringen). As we entered the town the American heavy artillery, our 155’s, started shelling the town from far behind our own lines. Fortunately none of them hit too close. They fell about one hundred yards to our right, but now we knew what it was like to be on the receiving end of our heavy stuff. We could hear them coming from a long way, and the explosions were terrific. We all hurried ahead to get out of the immediate area.

Further down the road we made a turn, and the two Germans who were our guards, shoved us into an unoccupied house and into the cellar for the night. Luckily we found a large vegetable bin with a few small, grubby, sandy potatoes in it. We hadn’t eaten since early that morning and we were all hungry enough to just brush off what sand and dirt we could with our fingers, and eat them, skin and all. It was clear to me that Wong was not going to be able to lay down and sleep with his arm hurting like it was, so he and I sat with our backs against the wall in that potato bin. He was a much smaller person than I was, so it was fairly comfortable with my arm around him, holding him to immobilize the arm, and try to keep him from shaking. We also shared body heat in this position. Somehow we all fell asleep.

Shortly after daybreak the two German soldiers who were to be our guards for that day rousted us out of the cellar. We were marched to the next town, not too far away (probably Wallersheim), and stopped in front of what appeared to be a schoolhouse. We hadn’t seen any civilians to this point. This is where our interrogation took place. We were sent inside, one at a time, before the interrogation officer. I think I was the third one to go in. Before me sat an impeccably dressed German officer. I wasn’t familiar enough with German uniform insignia to tell what rank he held. I guessed at least a Major.

One of the things that had been stressed to all GI’s in basic training was that, if captured, the only information you were required to give was your name, rank, serial number, and birth date. I was certainly surprised when this officer said, “Please, have a seat.” This came out in perfect English, without any trace of a German accent. Were it not for his uniform, I could have been talking to another American. He was filling out a form as we talked. When asked I gave him my name, rank, serial number, and birth date, which he filled in on the form. He then asked “What outfit are you with?” I replied “Sir, I am not required to give you that information.” “That’s OK,” he said, “I already know.” And with that remark he pulled open his desk drawer and took out a Fourth Infantry Division shoulder patch, and laid it on the desk. The drawer held many American unit patches and insignia in it. These Germans knew whom they were fighting. I finally screwed up enough courage to ask him where he learned to speak such perfect English. “I lived in New Jersey for eight years and went to college there,” he replied, “some day I want to go back.”

After questioning all of us, he came outside and informed us, almost apologetically, it seemed, that we would have to walk back into Germany, as they had no transportation for us, with the exception of Pvt. Wong, who would go back by truck, to a hospital. It was some comfort to know that his arm was finally going to be taken care of. We wished him well, and told him good bye. He managed a slight smile as he told us good bye. We never saw him again. I’m sure he made it back all right, as the war ended within three months, and his wound didn’t seem life threatening.

It was at this point we learned that there was a girl to be taken back into Germany with us. She was from Alsace Lorraine, the disputed territory between Germany and France. She had become pregnant by a German soldier and was being taken into Germany to have her child, so it would be born on German soil. It was also at this point we four prisoners were given our food parcels. They each consisted of one small loaf of black bread, a small amount of what they called margarine, but was nothing more than lard, and perhaps a ½ pound of ersatz (imitation) hard candy, individually wrapped. We were all as hungry as hell. All we had eaten in the last thirty hours was the few small, sandy, grubby potatoes the night before. It didn’t take us long to dig into the bread, and it didn’t taste too bad. I suppose anything would have tasted good at that point.

We started our trek east into Germany under the control of two guards. The only arms they carried were pistols. They were a little better dressed than the front line troops we had been in contact with. Being rear echelon troops however, didn’t make them any more friendly or gentle, as these two were just the opposite. We were roughly shoved into a column of two’s, and in the direction we were to go. The two guards and the girl fell in behind us. The pace they made us set was both fast and tiring. A time or two we whispered to one another to slow down a bit, which we did, but the guards caught on real fast and soon had us up to the original pace.

I find it difficult to remember the finer details of the three days forced march back into Germany as there was a certain likeness to all three. There are certain memories however, that do stand out in my mind, and I’ll list these as I recall them.

I had assumed, I suppose, that we would have the same guards all the way back to wherever we were headed, and was rather surprised of the fact that we were assigned a new pair of guards each morning. Thinking about it however, it wasn’t too unusual as each pair would have to report back to their own units. We were strictly at the mercy of the two guards we had each day, and we never knew what kind of people these would be, or what their feelings toward American POW’s would be. I can’t say we were ever harshly mistreated, but we were never treated to any kindness either, until the last day.

We hadn’t seen any German civilians up to this point, as we didn’t go through too many villages. The maps that the guards were using must have been highly detailed, as we would not stay on too many main roads, but rather use much smaller roads, and on occasion we would be on nothing more than a wide trail through the wooded areas. It was one of these trails that we all had a real scare. We were still moving in a column of two´s, with the two guards and the girl in the rear. Zimmerman and I were the front two. Suddenly two pistol shorts were fires. I thought we were being executed and turned around fully expecting to see Ferranti and McCollam both shot dead behind us, but there they stood, both just as surprised and scared as I was. Apparently firing off into the woods was one of the guard´s methods of cleaning his weapon. The girl seemed amused at our fright.

Getting back to the civilians I mentioned, our first encounter with them in the first town of any size, when they saw us marched by, ran out to the road with very angry looks on their faces, and asked the guards “Englisch? Englisch?” Nein! Nein!” the guard replied, “Americanish”. Upon learning we were Americans, much of the hostility would leave their faces. It was very apparent that they hated the English worse than they did the Americans.

At the end of this day’s march and after our evening meal of black bread and lard, we were placed in a barn for the night. We were to sleep in the haymow, so up the ladder we all went, the guards right behind us. Naturally they stayed between us and the ladder down to prevent us from escaping. We were dog-tired and it didn’t take us long to go to sleep. The guards didn’t even wait for us to go to sleep however, before they were taking advantage of the girl with them. They both had their turn, and I must add that she enjoyed the encounters as much as they did, from all the squealing and giggling that went on. This same thing occurred each night.

The following morning we had a rather pleasant experience, if anything could be pleasant under these conditions. Let me back track a bit and explain that there were quite a few political prisoners roaming loose, and not under guard, in this part of Germany. As we were eating our morning meal outside the barn, we were approached by two Serbian political prisoners who asked the guards if they could give us four Americans a haircut and a shave. The guards were agreeable, as their replacements hadn’t arrived. I had at least a week’s growth of whiskers on my face, and I have no idea when I last had a haircut. I can never forget that I had my first barber shave by a Serbian barber. These two Serbians were also in possession of Red Cross parcels which contained small, four cigarette packs of Old Gold cigarettes. Ferranti and I were the only ones that smoked, and they gave each of us a pack of four cigarettes. They must have been ages old, and as dry as a chip, as they crackled when rolled between my fingers. I lit up and inhaled a big drag or two and damn near fell on my face it made me so dizzy. Still I made those four cigarettes last as long as I could.

Let me get away from the story for a very short while and try to tell you of the very miserable conditions I had lived under since arriving in Europe. I arrived just in time to get into the Battle of the Bulge, and we were in contact with the enemy, with the exception of a few days until my capture. We slept in foxholes most every night, these would get very muddy if it rained or snowed. We were cold most of the time. The only chance we had to wash up a bit was if we were lucky enough to be billeted in an abandoned house or barn, and we could heat up some water in our steel helmets and at least shave, and wash to the waist. A bath or shower was out of the question. The clothing I was wearing during this time was two pair of wool long johns, two wool long sleeve undershirts. These articles I would alternate layers as they became progressively dirtier. (They were almost slick inside when I finally received a change.) I was also wearing wool OD pants and shirt, wool sweater, fatigue pants, wool lined field jacket, wool gloves, wool stocking cap under my helmet liner and helmet, wool socks and my snow-pac boots. It had been stressed upon us very strongly to keep our feet as dry as possible to prevents trench foot. I was in the habit of exchanging my wool socks every day and putting the damp pair inside my shirt around the waist, so that body heat would dry them. I went from Dec. 23, 1944 until Mar. 5, 1945 without a bath or shower. The above mentioned field jacket will enter into the story again later.

Back to the story. Up to this point I haven’t mentioned anything about my physical condition. In the army everything is “GI” or Government Issue, so my diarrhea at that time I called the “GI shits”, or the “GI’s”. As I recall now, both Zimmerman and I were bothered by this condition. This case of the “GI’s” led to what is probably the most embarrassing time of my life. When we would indicate to the guards, at least to the ones we had until this day, that we had to go, they would send us out into a field beside the road, where we could have a little bit of privacy and still keep a close eye on us. When I indicated to one of this day’s guards that I had to “go”, he pointed to the edge of the road. When I indicated that I wanted to go out into the field, he made it known to me very strongly that I was to “go” beside the road, about four feet away. Never, in my wildest imagination, would I ever take my pants down and take a “crap” in front of a girl, but at this moment I had no other choice. I don’t suppose the girl had ever seen this before either, but she seemed amused by my predicament. The other thing I particularly remember about this day occurred at the end of the day’s march. We had arrived at what looked like a small abandoned schoolhouse, where we were to spend the night. There were other prisoners (we learned later to be Russians), coming out the door, each carrying armloads of loose straw that they had apparently been sleeping on. We asked the guards, in our best German, why we couldn’t sleep on the straw, since we were going to take over these quarters. They indicated through scratching and bug picking motions that the straw was full of lice. When we got inside we could tell that this building had been used to house prisoners for a long time, as it had the wooden slat bunks that all ex-POW’s are familiar with. It was filthy dirty, and the Russians hadn’t removed every trace of the straw. I don’t think any of us were surprised to wake up scratching lice the next morning, as the cracks between the boards were probably full of them. I don’t recall, at this time, if the guards and the girl stayed in this building or not.

The next morning our luck took a turn for the better. As occurred every day, we were assigned new guards. One of these guards was also from Alsace Lorraine, and spoke French as well as German. Sgt. Ferranti spoke broken French, and this very much improved communication between the guards and us. This proved to be very significant later in the day.

The forced march this day still stands out in my memory very strongly. The day was dry but overcast, and rather cold. We were approaching a range of large wooded hills and the road started leading up. Early afternoon we began to by-pass a column of German soldiers, apparently retreating toward the Rhine. All of their equipment was on horse drawn wagons, loaded very heavily. Their artillery pieces were also being horse drawn. The progress of this column was very slow, as we were making much better time walking than they were. The horses were struggling very hard, and when one of them would falter and fall, and unable to get up again, the walking Germans would salvage what they could carry off the wagon, shoot the horse, and push it and the wagon over the edge and down the hill. I saw this occur four or five times. I felt sorry for the horses but there was no such feeling towards the Germans, seeing them in this situation. We finally completely passed this column, and continued our up hill march. The going wasn’t easy.

We finally emerged upon high ground with low rolling hills, and the road continued straight in an easterly direction. We arrived at a “T” intersection and turned north (left). After proceeding up this road about two miles, we passed a road leading east (right), however we proceeded north. About a mile and a half up this road we met another military column proceeding south, led by a German officer mounted on horseback. He made it known to our guards that there were American tanks in the distance behind this column. We turned back and proceeded down the road we had passed going east. This road led us into the town of Wehr (near Laacher See). As we entered the town what was most evident was the state of total confusion. There was a German with an axe, and he was chopping down a tall pole that had a Nazi swastika at it’s top. The townspeople and the German military personnel billeted in town were going in all directions, and the column we had met on the road were trying to make their way through town.

During this time our two guards made our presence as inconspicuous as they could. They placed us under a porch type overhang facing the street, while they contemplated what they were to do. The four of us knew what they were discussing between them. As we had approached the town we all began to hear the distant roar of the approaching armor. It was the sweetest sound I heard in some time. It was evident however, by the distance they were away, and the time of day, that they wouldn’t make the town by nightfall. This gave Sgt. Ferranti the opportunity to “go to work” on the French speaking guard, and try to convince him to stop here in this town that night, and after the armored column had passed through town, to surrender to us, and we would guarantee them safe passage back to the American lines. The only “fly in the ointment” to this was the fact that the other guard’s mother lived about twelve kilometres the other side of the Rhine river, and he wanted to see her.

While we were sitting under this porch with our backs to the wall, we attracted the attention of a few children. They were curious as to who we were and what we were carrying in our parcels. I don’t suppose these kids had seen candy for a long time, and when they found out what we had, they disappeared and returned shortly with apples they had apparently picket out of their cellars, and traded us apples for candy until the guards made them leave. A short time later we heard someone ask, “Would you like some split pea soup?” We all looked up, and he asked again. We said “yes” and he asked the guards. He was a German cook with his kitchen wagon across the street. His men had been fed and he had some soup left over. We were permitted to go, two at a time, with one guard, and we all had hot split pea soup. It was delicious.

A short time after we had returned to our places under the porch a German SS Trooper rode up on a very fine horse, and started shouting to the other German military around. He was very agitated, and we could tell that our presence was the topic of the conversation. We learned the next morning that he wanted the four of us executed, but was overruled, and out ranked, by the town military commander, an older Lt. Colonel. He will enter the story again later.

After the guards had made their decision as to what they were going to do, we proceeded toward the center of town, and turned to the right on a narrower street. We knew then that we were going to stay in this town that night. We proceeded down this street to the very last house on the left side. This house, like many, had a wall around it with a gate at the front.

As you can imagine, conditions had begun the change dramatically in our favor. This house belonged to an older German couple, and was occupied by them and two German soldiers who were billeted there. This made a total of eleven people spending the night there. The mood soon became almost party like. The older couple made hot chocolate for everyone, and passed out cigars. They even cranked up and old phonograph and played a Nelson Eddy and Janette McDonald recording of “Indian Love Call”. The spirits of us four Americans was very high. No one stood guard over us that night. If you had to go outside to relieve yourself, you went alone. The armored column had halted some distance from town, but they never let the Germans forget they were there, as they never shut the engines off, and would even rev them up now and then, to add to the din an roar of the many tanks.

At first light, the armored column started through the town of Wehr. We could plainly hear them roaring through on the main road, in the center of town. They didn’t come through in a solid column, but rather in small groups of three or four at a time. Our two guards gave us their pistols. The other German soldiers left their rifles inside, and we all went out into the courtyard in front of the house. We marched them out, with two of us on each side, into the street and towards the center of town. From each house, on both sides of the street, streamed something white out of their windows, in a sign of surrender. Also, from most every house, German soldiers billeted there would come out with their hands up and fall into the column we had. Needless to say, by the time we got close to the center of town we had quite a column of German soldiers marching down the street. This led to a tense, but rather amusing situation. We were approaching the main road when an observer in one of the tanks spotted this bunch of German soldiers coming down the road. The tank rocked to an immediate stop, and the turret with the 90mm cannon sticking out of it, moved around and was soon aimed right at us. “Hold your fire” we shouted, “there are Americans here”. With an astonished look on his face he asked, “What the f—k outfit are you guys with?” “The Fourth Infantry Division”, we answered. “How the f—k did you get up here?” was his next question. “We walked” was the only answer we could give. We then told him we had been prisoners of the Germans until this time and this group had surrendered to us. We asked him if they had any American weapons they could spare, as all we had were the pistols that had been surrendered to us by our guards. They didn’t have any to spare, but a short time later a jeep with an Armored Div. First Lieutenant drove up, and we repeated our story to him and he gave us a 30-cal carbine and a full clip of ammo. He then called back on his radio and made arrangements for a jeep to come up and pick us up and lead this bunch of prisoners back.

While we waited for transportation, we lined up all the Germans on one side of the street, against a building. Surrendering soldiers still were coming down all the streets leading into the center of town. Among them was the old Lt. Colonel, who, we had learned, had saved out “butts” the night before. Our guards had given us their packet containing our papers, and at this time we dug out the ones belonging to the girl with us, and gave them to her and turned her loose. We never knew what became of her. She seemed to be the self-sufficient type. I wonder to this day, if she and/or her child are still living.

A jeep to take us back finally arrived. We felt pretty good about the old German Colonel, so we decided to let him ride on the front fender of the jeep, as we led this column back. It became apparent very shortly that this was not going to work, as he started shaking like a leaf, probably from the cold and anxiety. We stopped and put him in the front seat of the jeep. I have forgotten which of the other three rode the rest of the way on the fender.

We had more or less put our two former guards “in charge” of the column walking behind us, and they did a pretty good job of keeping them in line and moving. After leaving the town, the column picked up more surrendering soldiers and political prisoners, coming out of the fields. When we arrived at the staging area we had more than 250 prisoners following us. The staging area was nothing more than a large open field. The few MP’s there asked us to help sort out this large group into their nationalities. The majority were Germans of course. The political prisoners were hard to tell, as most of them were wearing remnants if a ragged uniform of some kind. We would ask them if they were “Russki? Poleski?, Ukrainian?”, etc. and sort them out this way.

After a couple of hours or so helping the MP’s, they finally took us back to the Armored Division Headquarters. We had told the story of our capture and repatriation at every HQ we went through. At the Division Headquarters we met war correspondents from The Associated Press, to whom we told the complete story of our release. These stories made the local papers in the hometowns of the four of us in mid April. My wife, nor my parents, knew anything of my being a POW until the story came out in our local paper, as all my mail home was censored, and I had said nothing.

We were taken from the Armored Div. HQ to the 4th Infantry Div. HQ and on down through the chain of command leading to our own unit. While at the 4th Inf. Div. HQ we were de-loused and given new clothing after a good hot shower. This is where the field jacket I was wearing comes into the story again. While emptying the pockets, I found a bullet hole in the large pleat behind the left shoulder. A nice neat hole through both layers of the pleat. I borrowed a pocketknife and cut this portion of the jacket out. I still have it, and the pistol one of the guards handed to me, among my mementos. We had arrived at Division Headquarters just in time to stop the “missing in action” reports from our Company from going through. All of our “buddies” in Company F were very glad to see us again. One person in particular, Harold “Hap” Himmelman, of Reading Pa., had gone back up on Queen Hill, after it was finally taken, to look for my body, after he learned that the eight of our Company members had been executed. We became fast friends, and remain so to this day.

Here ends my story. I’ll add the following comment that I’ve made many times; I wouldn’t go through all my military experiences again for a million dollars, nor would I take a million dollars for having had them!”

Comments are closed.